In the early 2000s, researchers in text mining faced a familiar problem: scientific literature and patents were exploding in volume, but our ability to process them automatically and understand their content lagged far behind. Teams of scientists and engineers worked to extract meaning from this ocean of text, armed with the tools of the time; information retrieval, statistical (or more "analytical") Natural Language Processing (NLP), clustering algorithms, and carefully designed workflows.

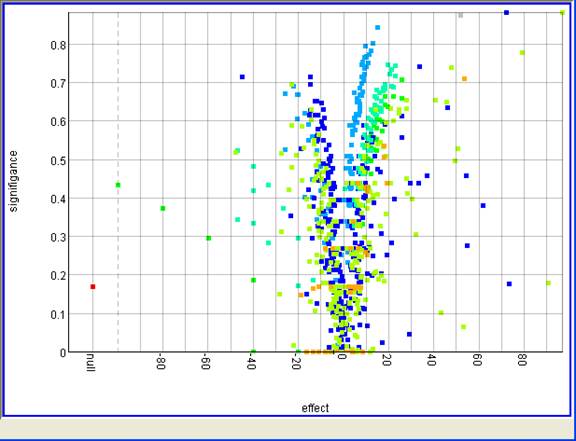

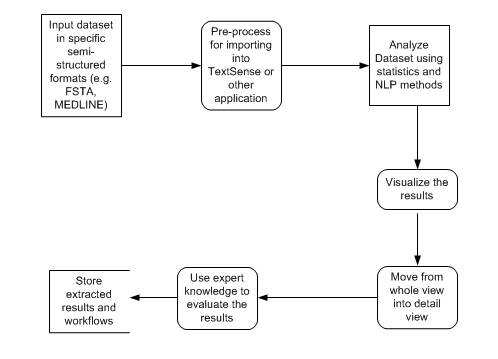

I am grateful that I had been introduced (by people that I still see as mentors) in information modelling and retrieval during my Engineering degree in the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (Greece). I then had the pleasure to work on text mining back in 2003 with a great team under the supervision of great people and scientists at Imperial College London and Unilever R&D. The goals were ambitious. We wanted to identify research trends through scientific papers and patents to spot innovation gaps, and track how concepts rose and fell through time. The methods reflected the state of the art. Documents were modelled as vectors, pre-processed and then single-word and multi-word terms were extracted, collocations identified, and co-occurrence statistics calculated. Modified versions of data-mining algorithms such as Apriori were repurposed to uncover associations. To extract the most useful words/phrases, we used volcano plots that highlighted which terms carried the meaning and importance. For temporal dynamics, we adapted finite automata to detect “bursts” - sudden spikes in the use of a concept that signaled an emerging trend.

This was labor-intensive science. Workflows were carefully assembled, statistical measures debated, visualizations interpreted with domain experts. It often felt like magic to extract insights from noisy text streams. And yet, these methods worked: they helped industry partners understand their competitive landscape, discover emerging technologies, and prioritize research investments. With limited computing power and limited automation, we pushed the boundaries of what was possible.

Two decades later, the contrast is striking. What once required bespoke workflows, overnight runs, and expert validation can now be achieved in "no-time" by large language models. Ask an LLM to summarize emerging research trends in a field, and it produces an elegant synthesis. Ask it to contrast two corpora, and it highlights the distinguishing features. Temporal trend analysis, once the domain of custom algorithms and visualizations, can be approached interactively with a single prompt. What took months of work in the early 2000s is now available on demand.

It would be easy to dismiss the past efforts as obsolete in light of today’s LLMs. But that would miss the point. Innovation is not a series of isolated miracles; it is a continuum. The co-occurrence rules, clustering experiments, and burst detection algorithms of two decades ago were not dead ends; they were some of the components on which today’s skyscrapers of AI were built. Each generation of researchers did the best it could with the knowledge and resources available, and in doing so laid the foundations for what followed.

The lesson is clear: what looks like magic today will look quaint tomorrow. Just as we now smile at the complexity of early text mining workflows compared to the fluency of modern LLMs, future scientists will one day smile at the limitations of our current models. Large language models are not the endpoint of text analysis, but another milestone along the path of discovery.

And that is the encouraging part. Science does not stop. Whether we call them AI systems, assistants, or simply tools, today’s models will become the raw material for the next revolutionary idea. The real challenge, and opportunity, is to keep asking new questions, to keep experimenting, and to remember that innovation is always built on the shoulders of the work that came before.

In the early 2000s, we mined text with statistical picks and shovels. Today, we have machines that move mountains of information effortlessly. Tomorrow, the tools will be more powerful still. The story of science is not one of endings, but of continuity, and the best chapters are yet to be written.